This example shows how to generate a greyscale constant-Q spectrogram image from an audio file using the Gaborator library.

We start off with some boilerplate #includes.

#include <memory.h> #include <iostream> #include <fstream> #include <sndfile.h>

The Gaborator is a header-only library — there are no C++ files

to compile, only header files to include.

The core spectrum analysis and resynthesis code is in

gaborator/gaborator.h, and the code for rendering

images from the spectrogram coefficients is in

gaborator/render.h.

#include <gaborator/gaborator.h> #include <gaborator/render.h>

The program takes the names of the input audio file and output spectrogram image file as command line arguments, so we check that they are present:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc < 3) {

std::cerr << "usage: render input.wav output.pgm\n";

exit(1);

}

The audio file is read using the libsndfile library

and stored in a std::vector<float>.

Note that although libsndfile is used in this example,

the Gaborator library itself does not depend on or

use libsndfile.

SF_INFO sfinfo;

memset(&sfinfo, 0, sizeof(sfinfo));

SNDFILE *sf_in = sf_open(argv[1], SFM_READ, &sfinfo);

if (! sf_in) {

std::cerr << "could not open input audio file: "

<< sf_strerror(sf_in) << "\n";

exit(1);

}

double fs = sfinfo.samplerate;

sf_count_t n_frames = sfinfo.frames;

sf_count_t n_samples = sfinfo.frames * sfinfo.channels;

std::vector<float> audio(n_samples);

sf_count_t n_read = sf_readf_float(sf_in, audio.data(), n_frames);

if (n_read != n_frames) {

std::cerr << "read error\n";

exit(1);

}

sf_close(sf_in);

In case the audio file is a stereo or multi-channel one,

mix down the channels to mono, into a new

std::vector<float>:

std::vector<float> mono(n_frames);

for (size_t i = 0; i < (size_t)n_frames; i++) {

float v = 0;

for (size_t c = 0; c < (size_t)sfinfo.channels; c++)

v += audio[i * sfinfo.channels + c];

mono[i] = v;

}

To make a constant-Q spectrogram, we will use a logarithmic

frequency scale, represented by a gaborator::log_fq_scale object.

To create a log_fq_scale, we must choose some

parameters: the frequency resolution, the frequency range, and

optionally a reference frequency.

The frequency resolution is specified as a number of frequency bands per octave. A typical number for analyzing music signals is 48 bands per octave, or in other words, four bands per semitone in the 12-note equal tempered scale.

The frequency range is specified by giving a minimum frequency;

this is the lowest frequency that will be included in the spectrogram

display.

For audio signals, a typical minimum frequency is 20 Hz,

the lower limit of human hearing. In the Gaborator library,

all frequencies are given in units of the sample rate rather

than in Hz, so we need to divide the 20 Hz by the sample

rate of the input audio file: 20.0 / fs.

Unlike the minimum frequency, the maximum frequency is not given explicitly — instead, the analysis always produces coefficients for frequencies all the way up to half the sample rate (a.k.a. the Nyquist frequency). If you don't need the coefficients for the highest frequencies, you can simply ignore them.

If desired, one of the frequency bands can be exactly aligned with

a reference frequency. When analyzing music signals, this is

typically 440 Hz, the standard tuning of the note A4.

Like the minimum frequency, it is given in

units of the sample rate, so we pass 440.0 / fs.

Let's construct a log_fq_scale:

gaborator::log_fq_scale scale(48, 20.0 / fs, 440.0 / fs);

The frequency scale forms a part of the spectrum analysis parameters,

which are stored in an object of type gaborator::parameters.

In this example, there is no need to specify parameters other than the

frequency scale, so the parameters can be constructed simply by calling

the gaborator::parameters constructor with the frequency scale

as an argument:

gaborator::parameters params(scale);

Next, we create an object of type gaborator::analyzer;

this is the workhorse that performs the actual spectrum analysis

(and/or resynthesis, but that's for a later example).

It is a template class, parametrized by the floating point type to

use for the calculations; this is typically float.

Constructing the gaborator::analyzer involves allocating and

precalculating all the filter coefficients and other auxiliary data needed

for the analysis and resynthesis, and this takes considerable time and memory,

so when analyzing multiple pieces of audio with the same

parameters, creating a single gaborator::analyzer

and reusing it is preferable to destroying and recreating it.

gaborator::analyzer<float> analyzer(params);

The result of the spectrum analysis will be a set of spectrogram

coefficients. To store them, we will use a gaborator::coefs

object. Like the analyzer, this is a template class parametrized

by the data type. Because the layout of the coefficients is determined by

the spectrum analyzer, it must be passed as an argument to the constructor:

gaborator::coefs<float> coefs(analyzer);

Now we are ready to do the actual spectrum analysis,

by calling the analyze method of the spectrum

analyzer object.

The first argument to analyze is a float pointer

pointing to the first element in the array of samples to analyze.

The second and third arguments are of type

int64_t and indicate the time range covered by the

array, in units of samples. Since we are passing the whole file at

once, the beginning of the range is sample number zero, and the end is

sample number mono.size(). The fourth argument is a

reference to the set of coefficients that the results of the spectrum

analysis will be stored in (or to be precise, added to).

analyzer.analyze(mono.data(), 0, mono.size(), coefs);

Now there is a set of spectrogram coefficients in coefs.

To render them as an image, we will use the function

gaborator::render_p2scale().

Rendering involves two different coordinate spaces: the time-frequency coordinates of the spectrogram coefficients, and the x-y coordinates of the image. The two spaces are related by an origin and a scale factor, each with an x and y component.

The origin specifies the point in time-frequency space that corresponds to the pixel coordinates (0, 0). Here, we will use an origin where the x (time) component is zero (the beginning of the signal), and the y (frequency) component is the band number of the first (highest frequency) band:

int64_t x_origin = 0;

int64_t y_origin = analyzer.bandpass_bands_begin();

render_p2scale() supports scaling the spectrogram in

both the time (horizontal) and frequency (vertical) dimension, but only

by power-of-two scale factors. These scale factors are specified

relative to a reference scale of one vertical pixel per frequency band

and one horizontal pixel per signal sample.

Although a horizontal scale of one pixel per signal sample is a mathematically pleasing reference point, this reference scale is not used in practice because it would result in a spectrogram that is much too stretched out horizontally. A more typical scale factor might be 210 = 1024, yielding one pixel for every 1024 signal samples, which is about one pixel per 23 milliseconds of signal at a sample rate of 44.1 kHz.

int x_scale_exp = 10;

To ensure that the spectrogram will fit on the screen even in the case of a long audio file, let's auto-scale it down further until it is no more than 1000 pixels wide:

while ((n_frames >> x_scale_exp) > 1000)

x_scale_exp++;

In the vertical, the reference scale factor of one pixel per frequency band is reasonable, so we will use it as-is. In other words, the vertical scale factor will be 20.

int y_scale_exp = 0;

Next, we need to define the rectangular region of the image coordinate space to render. Since we are rendering the entire spectrogram rather than a tile, the top left corner of the rectangle will have an origin of (0, 0).

int64_t x0 = 0;

int64_t y0 = 0;

The coordinates of the bottom right corner are determined by the

length of the signal and the number of bands, respectively, taking the

scale factors into account.

The length of the signal in samples is n_frames,

and we get the number of bands as the difference of the end points of

the range of band numbers:

analyzer.bandpass_bands_end() - analyzer.bandpass_bands_begin().

The scale factor is taken into account by right shifting by the

scale exponent.

int64_t x1 = n_frames >> x_scale_exp;

int64_t y1 = (analyzer.bandpass_bands_end() - analyzer.bandpass_bands_begin()) >> y_scale_exp;

The right shift by y_scale_exp above doesn't actually

do anything because y_scale_exp is zero, but it would be

needed if, for example, you were to change y_scale_exp to

1 to get a spectrogram scaled to half the height. You could also make a

double-height spectrogram by setting y_scale_exp to -1,

but then you also need to change the

>> y_scale_exp to

<< -y_scale_exp since you can't shift by

a negative number.

We are now ready to render the spectrogram, producing

a vector of floating-point amplitude values, one per pixel.

Although this is stored as a 1-dimensional vector of floats, its

contents should be interpreted as a 2-dimensional rectangular array of

(y1 - y0) rows of (x1 - x0) columns

each, with the row indices increasing towards lower

frequencies and column indices increasing towards later

sampling times.

std::vector<float> amplitudes((x1 - x0) * (y1 - y0));

gaborator::render_p2scale(

analyzer,

coefs,

x_origin, y_origin,

x0, x1, x_scale_exp,

y0, y1, y_scale_exp,

amplitudes.data());

To keep the code simple and to avoid additional library

dependencies, the image is stored in

pgm (Portable GreyMap) format, which is simple

enough to be generated with just a few lines of inline code.

Each amplitude value in amplitudes is converted into an 8-bit

gamma corrected pixel value by calling gaborator::float2pixel_8bit().

To control the brightness of the resulting image, each

amplitude value is multiplied by a gain; this may have to be adjusted

depending on the type of signal and the amount of headroom in the

recording, but a gain of about 15 often works well for typical music

signals.

float gain = 15;

std::ofstream f;

f.open(argv[2], std::ios::out | std::ios::binary);

f << "P5\n" << (x1 - x0) << ' ' << (y1 - y0) << "\n255\n";

for (size_t i = 0; i < amplitudes.size(); i++)

f.put(gaborator::float2pixel_8bit(amplitudes[i] * gain));

f.close();

To make the example code a complete program,

we just need to finish main():

return 0;

}

If you are using macOS, Linux, NetBSD, or a similar system, you can build

the example by running the following command in the examples

subdirectory.

You need to have libsndfile installed and supported by

pkg-config.

c++ -std=c++11 -I.. -O3 -ffast-math $(pkg-config --cflags sndfile) render.cc $(pkg-config --libs sndfile) -o render

The above build command uses the Gaborator's built-in FFT implementation,

which is simple and portable but rather slow. Performance can be

significantly improved by using a faster FFT library. On macOS, you

can use the FFT from Apple's vDSP library by defining

GABORATOR_USE_VDSP and linking with the Accelerate

framework:

c++ -std=c++11 -I.. -O3 -ffast-math -DGABORATOR_USE_VDSP $(pkg-config --cflags sndfile) render.cc $(pkg-config --libs sndfile) -framework Accelerate -o render

On Linux and NetBSD, you can use the PFFFT (Pretty Fast FFT) library. You can get the latest version from https://bitbucket.org/jpommier/pffft, or the exact version the example code was tested with from gaborator.com:

wget http://download.gaborator.com/mirror/pffft/7641e67977cf.zip unzip 7641e67977cf.zip mv jpommier-pffft-7641e67977cf pffft

Then, compile it:

cc -c -O3 -ffast-math pffft/pffft.c -o pffft/pffft.o

(If you are building for ARM, you will need to add -mfpu=neon to

both the above compilation command and the ones below.)

PFFFT is single precision only, but it comes with a copy of FFTPACK which can be used for double-precision FFTs. Let's compile that, too:

cc -c -O3 -ffast-math -DFFTPACK_DOUBLE_PRECISION pffft/fftpack.c -o pffft/fftpack.o

Then build the example and link it with both PFFFT and FFTPACK:

c++ -std=c++11 -I.. -Ipffft -O3 -ffast-math -DGABORATOR_USE_PFFFT $(pkg-config --cflags sndfile) render.cc pffft/pffft.o pffft/fftpack.o $(pkg-config --libs sndfile) -o render

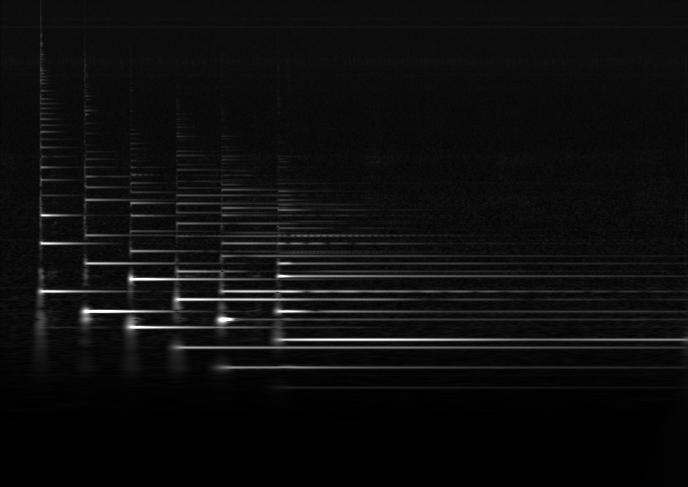

Running the following shell commands will download a short example

audio file (of picking each string on an acoustic guitar), generate

a spectrogram from it as a .pgm image, and then convert

the .pgm image into a JPEG image:

wget http://download.gaborator.com/audio/guitar.wav ./render guitar.wav guitar.pgm cjpeg <guitar.pgm >guitar.jpg

The JPEG file produced by the above will look like this: